By Chris Irwin, J2 Innovations.

By Chris Irwin, J2 Innovations.

When a technology is new, it is usually very expensive and proprietary because it is difficult to achieve and complex to deliver. This was certainly true of computers; which were hugely expensive compared to now and each manufacturer offered systems that were unique to them, because they designed all the elements; the software, firmware and hardware.

As we now know well, decisions by the likes of IBM and Microsoft, plus developments such as the Linux Foundation and the opens source software movement, have led to a very different world for computing technology. Those of you who, like me, have spent our careers in the controls industry will recognise many parallels, and some significant differences.

The development of open protocol standards

The use of computers to control buildings was an inevitable consequence of the falling cost of the technology and the huge increase in the complexity of the equipment required to achieve comfort in large modern buildings. As with computers, the nascent BMS market was initially supplied by manufacturers who offered highly-proprietary systems which only they could install and maintain. As the technology matured, so the software to program the required control logic was made easier. As a result, a wider range of people could provide the engineering. Meanwhile, pressure from end users, who didn’t want to be tied to only one manufacturer for the life of the building or campus, led to the development of open protocol standards that could enable one manufacturers’ system to talk to another.

However, since the way buildings are contracted tends to require a functionally-biased packaging of sub-contracts, each piece of controls equipment in a building developed separately, and each sub-sector developed its own standards. The result today is a plethora of ‘standard’ protocols which are used by the various sub-systems in a building; BACnet for HVAC, DALI and KNX for lighting, Modbus for electrical metering and power management, M-Bus for heat metering etc. Some protocols such as LONworks did manage for a while to gain traction in multiple segments, but its adoption has declined in recent years. So, although people still dream of there being ‘one standard to rule them all’, the reality is much messier, and the challenge of how to get systems talking to one another has not gone away.

Communicating between systems

Don’t get me wrong; the widespread specification and adoption of the open standards listed above have made life a lot easier for BMS engineers, but such communications standardisation is only solving part of the problem. Whenever two systems try to interact, there is a significant amount of engineering time required to ensure that the data from one system is being properly understood by the other and correctly reported to the supervisory software that is generally used as a window on the building’s performance; to display floor plans, plant schematics, dashboard and reports.

Imagine a world in which such inter-communication between systems happened automatically without requiring manual intervention and where all the building’s data can be visualised in the required format with relatively little engineering effort!

The key is to provide context to the data which is being communicated between systems; now commonly referred to as ‘tagging’. Various initiatives have been attempted, and some of the protocol standards such as LONworks and BACnet have developed the concept of profiles, defining much of the metadata associated with a real-world data point. Unfortunately, these profile approaches have not been sufficient for computers to fully automate the inter-linking of systems.

Project Haystack

Over the last few years, an open source initiative called Project Haystack has sought to fully solve this tagging requirement for buildings. Project Haystack is now gaining significant traction globally, and is in discussion with ASHRAE (the originators of the BACnet standard) and Brick (a more recent IT-inspired initiative) to see how a common approach can be agreed. In systems in which all the data is tagged, it is then possible to almost fully-automate the generation of plant schematics, floorplans, dashboards, alarms and energy reports, as well as deliver real-time fault and performance analytics.

Open frameworks based on the concept of tagging

This is why open frameworks matter. Currently, none of the BMS, lighting, fire detection and other manufacturers of control and monitoring equipment for buildings have developed software in their proprietary systems that natively enables such tagging, nor do they provide a way to automate the management of the data from multiple system sources. Open frameworks are designed from the ground up to handle data from multiple sources and protocols, which makes the process of engineering integrated systems with common visualisation much easier.

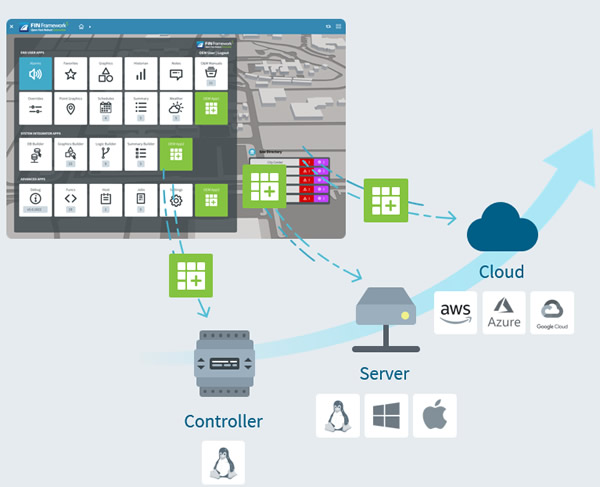

The increasing use and specification of the Niagara Framework from Tridium and its partners is testimony to the success of the open framework approach. Recently, Tridium has also added a tagging capability with specific support for the Haystack standard. Meanwhile, J2 Innovations’ FIN framework takes this several steps further, as it has been developed completely based on the concept of tagging using Haystack; so, for the first time, automation of the graphics creation, alarms, dashboards and reports has become a reality. This offers a huge time saving in the engineering of the BMS and related building systems, and creates the potential for new functionality and diagnostics.

Until the advent of tagging and the Haystack standard, the message definition was defined by the protocol used, and these are specific to the building controls sector. Now, open framework software such as FIN can ‘read’ data from any system, regardless of protocol, provided it is communicated over IP using an agreed transport mechanism such as MQTT, JSON or a REST API – all standards used by IT systems in many other sectors. As the use of Haystack grows, the scope of the agreed tags will extend well beyond building services systems, to encompass business software, such as, meeting room and hot desk booking, CAFM/CMMS (Computer-Aided Facility Management/Computerised Maintenance Management System), asset management, car parking, etc.

Accelerating innovation

Since buildings last a long time, and installed electronic systems are expected to have a lifecycle of 10-15 years, it is perhaps unsurprising that our industry has been somewhat slow to respond to the changes that have been occurring in the broader computing world. For many years now, computer software has been de-coupled from the hardware by the use of common operating systems, such as, Windows, Unix and Linux, with JVMs (Java Virtual Machines) providing some assistance with the portability of software onto embedded hardware platforms. This trend has led to an acceleration of innovation and created much more flexibility and competition in the market.

In the building controls sector we are, as yet, some way off from embracing this de-coupling shift, which affects most of the products used at the edge (the primary data collection and/or control devices), although, at the global controller level, both Niagara and FIN have been ported by various OEM controls partners. FIN Framework can run on a JVM on very small low-cost platforms such as the Raspberry Pi or Beaglebone platforms, which cost as little as US$10. A new version to be released next year will reduce further the processor and memory requirements, making it suitable for even smaller hardware platforms. Clearly, the technology is there for when the equipment and controls manufacturers want it.

Conclusion

There is now little doubt that the future for the buildings sector will be open systems using a tagging standard connected via IP networking and IT-derived messaging standards, with hardware largely independently available from the software that provides the application. The current paradigm proposed by the big controls players such as Siemens, Honeywell and Schneider, uses proprietary hardware and software which requires intensive system engineering and locks-in the customer for the maintenance and upgrades. This approach will give way to systems that use open framework software to ‘glue’ multiple devices and systems together, with largely automated configuration processes.

Chris Irwin is the VP Sales EMEA & Asia at J2 Innovations, a wholly owned subsidiary of Siemens AG, based in California. J2 Innovations created FIN Framework, a state-of-the-art open framework for building automation and IoT applications.